Stoic System of Philosophy

The early Stoic philosophical system was structured into key areas such as the topic of philosophy, the virtues, the passions and their sub-divided parts. Zeno the founder of Stoicism originated the tri-partition division of philosophy, which includes the three fields of study – Logic, Physics and Ethics. Epictetus introduced the three disciplines of Desire, Action and Assent which directly play into the over arching system of Stoic philosophy. We can begin by defining the fields below for further exploration and how they integrate with one another as the underlying foundation for the Stoic system of philosophy.

Three Fields of Study

Stoicism included three main areas of study:

- Logic (modern logic, proper, rhetoric, epistemology and cognitive science)

- Physics (modern natural science, metaphysics and theology)

- Ethics (the study of how live your best life)

In “Lives of the Eminent Philosophers” a rich anecdotal introduction to the major and minor figures of ancient Greek Philosophy, Diogenes Laertius references the three parts:

“I have decided to give a general account of all the Stoic doctrines in the life of Zeno because he was the founder of the School. I have already given a list of his numerous writings, in which he has spoken as has no other of the Stoics. And his tenets in general are as follows.” (DL, VII.38)

“Philosophic doctrine, say the Stoics, falls into three parts: one physical, another ethical, and the third logical. Zeno of Citium was the first to make this division in his Exposition of Doctrine.” (DL, VII.39)

“Philosophy, they say, is like an animal, Logic corresponding to the bones and sinews, Ethics to the fleshy parts, Physics to the soul. Another simile they use is that of an egg : the shell is Logic, next comes the white, Ethics, and the yolk in the centre is Physics. Or, again, they liken Philosophy to a fertile field : Logic being the encircling fence, Ethics the crop, Physics the soil or the trees. Or, again, to a city strongly walled and governed by reason.

No single part, some Stoics declare, is independent of any other part, but all blend together. Nor was it usual to teach them separately. Others, however, start their course with Logic, go on to Physics, and finish with Ethics ; and among those who so do are Zeno in his treatise On Exposition, Chrysippus, Archedemus and Eudromus.” (DL, VII.40)

STOIC LOGIC

Stoic logic was a form of propositional logic developed by Chrysippus in the 3rdcentury B.C.E.. Chrysippus’s logic differed from Aristotle’s term logic because it was based on the analysis of propositions rather than terms. For the ancients Logic included anything remotely connected to rational thought. Ancient logic included all of what we now call rhetoric, grammar, semantics, logic proper, and epistemology. The Stoics provided a system of natural deduction based on five (axiomatic) rules of inference. This system has two parts: propositions and inference rules that act upon them.

Below is a brief outline of the systematic components that make up Stoic logic. Aside from the technical semantics the end goal was to arrive at rational value judgements based on true or false conclusions. This system provided a process for sound reason thus laying a foundation to make progress into the other two branches of study, “Physics” and “Ethics”.

Propositions

Logic for the Stoics included a wide field of interrelated study in the areas of language, grammar, rhetoric and epistemology.

Assertibles

Stoic logic begins with statements or simple propositions that are either true or false. They called these statements “assertibles” which are much like modern propositions, but their truth value can change depending on when they are asserted.

Compound Assertibles

Simple assertibles can be connected to each other to form compound or non-simple assertibles. This is achieved through the use of logical connectives. Chrysippus seems to have been responsible for introducing the three main types of connectives: the conditional(if), conjunctive(and), and disjunctive (or). The later period Stoics added more connectives: the pseudo-conditional took the form of “since p then q”; and the casual assertible took the form of “because p then q”. There was also a comparative (or dissertive): “more/less (likely) p than q”. Here’s an example of Logical Connectives in use, with the name of the connective in italics, the type of connective in bold and a sentence illustrating its use:

Conditional: if it is day, it is light

Conjuction: it is day and light

Disjunction: either it is day ornight

Pseudo-conditional: since it is day, it is light

Casual: because it is day, it is light

Comparative: more likely it is day than night

Modality

Assertibles can also be defined by their modal properties – whether they are possible, impossible, necessary, or non-necessary. Chrysippus took a middle position between the modal systems of Diodorus and Philo combining elements of both:

Chrysippus’s Modal Definitions

possible: An assertible which can become true and is not hindered by external things from becoming true

impossible: An assertible which cannot become true or which can become true but is hindered by external things from becoming true

necessary: An assertible which (when true) cannot become false or which can become false but is hindered by external things from becoming false

non-necessary: An assertible which can become false and is not hindered by external things from becoming false.

Syllogistic Arguments

In Stoic logic, an argument form contains two (or more) premises related to one another as cause and effect. An example of a typical Stoic syllogism is:

If it is day, it is light; (first premiss/non-simple assertibe)

It is day; (second premiss/simple assertible)

Therefore it is light.

In more formal terms this type of syllogism is:

If p, then q;

p;

Therefore q.

Like Aristotle’s term logic, Stoic logic uses variables, but the values of the variables are propositions not terms. Chrysippus created five basic argument forms, which he deemed as true beyond question. These five indemonstrable arguments are made up of conditional, disjunction, and negation conjunction connectives, and all other arguments are reducible to these five indemonstrable arguments.

Indemonstrable Arguments

Modus ponens

Description: If p, then q. p. Therefore, q.

Example: If it is day, it is light. Therefore, it is light.

Modus tollens

Description: If p, then q. Not q. Therefore, not p.

Example: If it is day, it is light. It is not light. Therefore, it is not day.

Description: Not both p and q. p. Therefore, not q.

Example: It is not both day and night. It is not day. Therefore, it is night.

Modus tollendo ponens

Description: Either p or q. Not p. Therefore, q.

Example: It is either day or night. It is not day. Therefore, it is night.

Modus ponendo tollens

Description: Either p or q. p. Therefore, not q.

Example: It is either day or night. It is day. Therefore, it is not night.

These are the basic building blocks of formal arguments and demonstrations for the Stoics. Arguments prove that something is rather obvious, while a demonstration starts with an obvious premise and leads us to an unexpected result.

Analysis

There are many arguments that are not in the form of the five indemonstrables, and the goal is to illustrate how they can be reduced to one of the five types. Below is a simple example of Stoic reduction by Sextus Empiricus:

If both p and q, then r;

not r;

but also p;

Therefore not q

Paradoxes

The Stoics also engaged in the subject of the enumeration and refutation of false arguments, and in particular of paradoxes. Part of the Prokopton’s training was to prepare the philosopher for paradoxes and help find solutions.

Stoic Practice in Logic

The Stoics were relentless in their practice of logic applied to problems in everyday life. For this reason logic was not limited to an abstract theory of reasoning and cataloging but rather diligent daily use. Thus to provide sound logic required mastery of one’s inner self, to be a true warrior of the mind.

Stoic training in logic included the study of paradoxes, the dissection of arguments and a mastery of logical puzzles.

STOIC PHYSICS

Physics to the Stoics by today’s modern interpretation would encompass natural science and metaphysics. Stoic physics shared the idea that the universe began in a cosmic fire and through a process of regeneration would end and renew in the same fashion. They believed in causation as a universal phenomenon and that events don’t merely happen, but they happen and have a cause. Furthermore, the Stoics believed in the crucial concept that according to their physics life ought to be lived in accordance with nature which can be interpreted as “in agreement with what Zeus (God) has ordained,” or live in accordance with reason. The Stoics believed that the universe was organized by a set of rational principles, which governed all things. They called this the Logos and believed that a part of the divine cosmos existed in all of us.

The Stoics identified the universe and God with Zeus. The Stoic God is not a transcendent being standing outside of nature but instead immanent. The divine element is immersed in nature itself.

STOIC ETHICS

The Stoics did not seek to be emotionless, but rather they sought to transform their emotions by a resolute “askësis“ enabling a person to develop clear judgement and inner calm. They taught freedom from passion by following reason. The Stoics believed in the cultivation of one’s moral virtues in order to become a good person and experience Eudaimonia (often translated as “flourishing”) The four cardinal virtues recognized by the Stoics were:

Four Cardinal Virtues

Prudence or Practical Wisdom

(Phronesis), sometimes just called Wisdom (Sophia), which opposes the vice of “ignorance”.

Justice or Integrity

(Dikaiosune), which opposes the vice of “injustice”

Fortitude or Courage

(Andreia), which opposes the vice of “cowardice”

Temperance or Moderation

(Sophrosune), which opposes the vice of “wantonness”

The four cardinal virtues defined as forms of knowledge can be defined as (q.v., Stobaeus in Early Stoics, p. 125-130):

Prudence- is knowledge of which things are good, bad, and neither; or “appropriate acts”.

Temperance- is knowledge of which things are to be chosen, avoided, and neither; or stable “human impulses”.

Justice- is the knowledge of the distribution of proper value to each person; or fair “distributions”.

Courage- is knowledge of what is terrible, what is not terrible, and what is neither; or “standing firm”.

The Stoics taught to transmute emotions and their judgements of events to achieve equanimity and inner calm. By accurately assessing situations with the ruling faculty of their mind they could analyze the emotion in question and decide whether they should give assent or dissent to the emotion.

The Stoics believed that emotions of Fear, Anger or Love are instinctive human reactions that cannot be avoided based on certain situations. To help achieve peace of mind or apatheia resulting from clear judgement the Stoics distinguished between propathos (instinctive reaction) and eupathos (feelings resulting from correct judgement).

STOIC PASSIONS

In order to achieve apatheia the practicing Stoic must be able to discern between Eupatheiai (healthy passions) and Pathe (unhealthy passions). To understand the passions better, Massimo Pigliucci does an excellent breakdown of the passions, positive vs. negative:

PREFERRED & DISPREFERRED INDIFFERENTS

An important Stoic idea was the distinction of preferred and dispreferred “indifferents”. Wealth, health and other material goods are indifferent with respect to them having no bearing on one’s character from a moral and virtuous standpoint (i.e., the decision to be morally upright is in the control of the person regardless of their station in life). However, some indifferents are preferred as they assist us in realizing our goals while others that would cause us to detour from our plans or hinder our progress would be categorized as dispreferred.

The following list of indifferent things by Chrysippus and other Stoics being neither good nor bad, are listed as pairs of opposites (Diogenes Laertius, 7.102):

- Life and death

- Health and disease

- Pleasure and pain

- Beauty and ugliness

- Strength and weakness

- Wealth and poverty

- Good reputation and bad reputation

- Noble birth and low birth

- …and other such things.

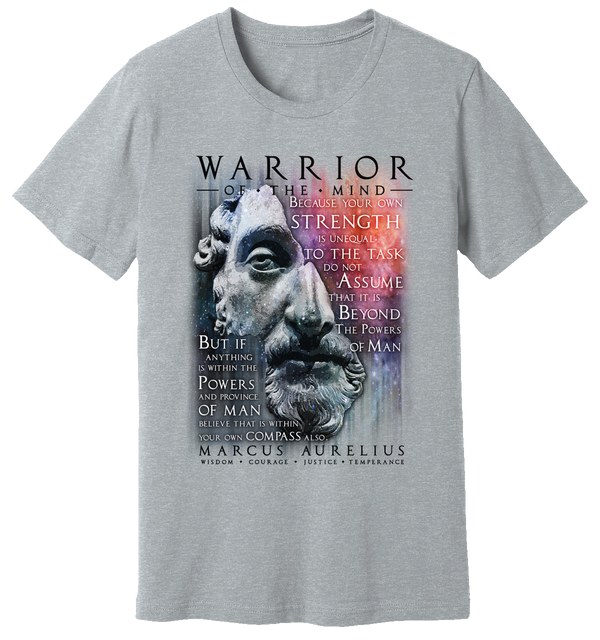

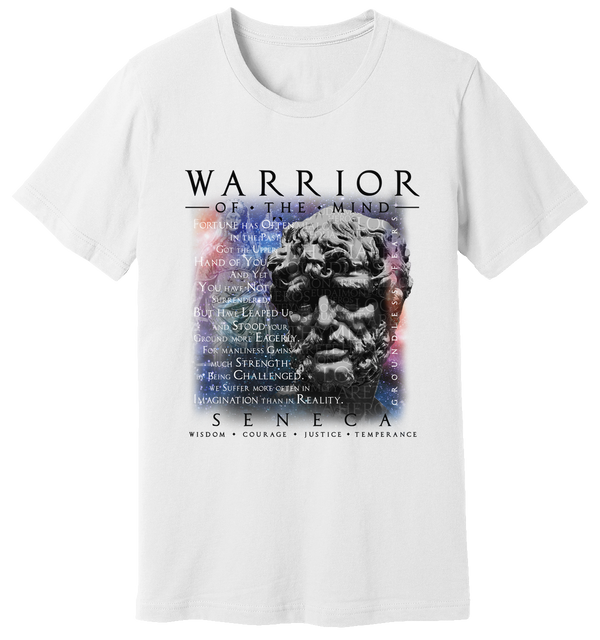

Featured collection

Warrior Invocation II

WARRIOR INVOCATION II, RULE YOUR DAY by setting your state to the proper frequency. Invoke and AWAKEN THE WARRIOR WITHIN!!